The following reflection is offered by Professor Anne Carpenter of the Theology and Religious Studies Department of Saint Mary’s College

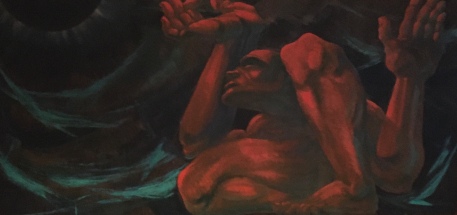

I have been asking myself what it is that I can do, what wisdom the Christian tradition that I know can give us in these frightening times. And it has occurred to me that I do not know what to say, nor how – exactly – Catholicism can be the morning star in the dark. “I am weary with crying out; my throat is parched. My eyes fail, from looking for my God” (Ps 69:4).

Would that I could say, “Look now: God is around the corner.” (As if God hid in corners?) Or that I could say, “It will be okay.” It is not okay; we are not okay; the world is not okay; and I am obligated not to make of faith an anesthetic lie. My task, instead, is to look at the Christian tradition for evidence of what it is that we might do, and how we might understand the context of that task.

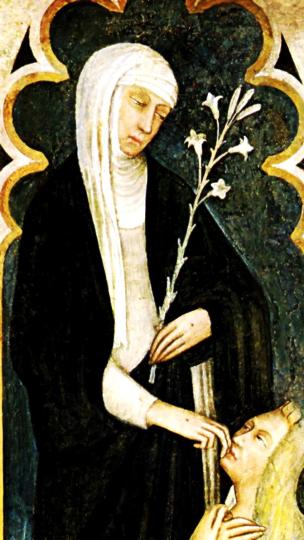

Catherine of Siena, who lived during the Plague, reminds us time and again that love of God and love of neighbor form one and the same love. “Your duty,” says God the Father in her Dialogue, “is to love your neighbors as your own self.” Catherine has good Scriptural warrant here. But her thought is also complex, since these loves – of God, of neighbor – imply one another, and since for her to lack one is to lack the other. “If you do not love me, you do not love your neighbors.”[1]

When I think of what Catherine might mean here, underneath the simple boldness of her claim, I think of that Christian conviction that every human being is not just significant, but also eternally significant. It is so easy to say. Enough to make it mere dust. When I really think of it, this love, this eternal significance of the person, I think of the radical love required to greet such significance, and I am at a loss. Surely I am not capable of anything like the eternal, nor the infinite. But this is why Catherine cleaves one love to the other, why love for God – and the gift of God’s own love for that love – is alone what can rise to the task of really loving one’s neighbor as they deserve. Even when that neighbor looks back in the mirror.

And this memory of my neighbor must follow me through my days, now most of all. When I am frustrated at interminable stay-at-home orders, when I am concerned for the future, when everything in me revolts at the thought of another Zoom anything: I must hold my neighbor in mind. Because I am not at home for simply myself. The future under threat is ours, and not just mine. I have students to care for, or classes to attend. All of which forces me out of the delusion of my egoism.

If I can – and this is hard – my heart must hold a flame for my neighbor at all times. I do not say that this will ease any difficulties. I do say that it is orienting, that it roots me in the direction of God’s own gaze, which is toward the world, and toward my neighbor.

Catherine also counsels us time and again to courage. “You must,” God tells her, “follow the way [of life] courageously, not in the fog but with the light of faith that I gave you.”[2] Catherine here invokes very old ideas: both testaments emphasize a certain courage and endurance, in particular before suffering and persecution (for example, Jn 16:33).

We might more nearly associate Catherine’s “courage” with one of the seven traditional gifts of the Holy Spirit, in particular with fortitude. The basic idea behind the gifts of the Spirit is that God gives us gifts of virtues because we need help living holy lives. In general, the Holy Spirit is the Person of the Trinity that Christians associate with sanctity, and therefore the Spirit is associated with the help that we need to live our lives before the Father in the image of Christ. “He [the Spirit] perfects all other things,” says Basil the Great, “and Himself lacks nothing; He gives life to all things, and is never depleted.”[3]

Fortitude is, perhaps, not one of the more famous of the virtues associated with the Spirit, like wisdom or counsel, but Catherine seems to have the right idea for times such as ours. Christians, and therefore Christian institutions, are called to fortitude in the face of trials. Or, as Thomas Aquinas says, “fortitude in the face of the fearful dangers.”[4] Fortitude does not just mean courage; it also means a kind of endurance. Now, because all virtues imply each other, this endurance must be humble and not foolish, it must be honest and not deceitful, it must be attentive, intelligent, reasonable, responsible, and loving.

This is hard to be. Our temptation will be to lie to ourselves or others. Our temptation will be to allow decisions to be made despite us instead of together. Our temptations will be many, and our task is to endure, which is to say to stand and to meet each hour with exactly what that hour requires. This is our terrible, wonderful task. It is all God asks of us, and it is everything.

[1] Catherine of Siena, Dialogue, 33.

[2] Catherine of Siena, Dialogue, 70.

[3] Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, 43.

[4] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I-II.68.4

Photo credits: Brother Charles and Wikimedia Commons

This is beautiful.

Thank you, Anne, for your inspiring words that both console and edify us. Brother, Charles, thank you for the art that adds to the text. I am thinking of a trip to Mission Delores when it is possible to go. Blessings!

LikeLike

Thank you Anne! Very inspirational during this difficult and uncertain time.

LikeLike